When you’re winding down a company, the to‑do list can feel endless. Customers need updates, employees need care, and investors want a plan. In that swirl, sales tax often hides in plain sight - until it sparks delays or, worse, personal exposure for the people who ran the business. If your company ever collected sales tax, you need a clear, methodical approach before you dissolve. This guide explains why sales tax matters so much in a shutdown, what to check, and how to close things out the right way. It’s general information, not legal or tax advice; every state is different, so loop in a tax professional for state‑specific steps.

Why Sales Tax Matters so Much During a Shutdown

Sales tax is a “trust” tax in many states. That means the money you collected at checkout never belonged to your business - it belonged to the state, and you held it in trust. Nebraska’s regulation puts it plainly: sales tax collected “is a trust fund held by the collector that belongs to the state”, even if collected in error. Washington’s Department of Revenue says the same: sales tax you collect is a trust fund that must be remitted. Ohio’s tax department likewise describes sales tax as a trust tax to be collected and paid over. These are not technicalities; they shape how states define unpaid balances and who they can pursue.

Because it’s a trust tax, unpaid or unfiled sales tax can pierce the corporate shell. New York’s Tax Law §1133 imposes “responsible person” liability on certain owners, officers, and employees who control the collection and remittance of sales tax. In a 2020 memorandum, New York’s tax department highlighted that such individuals can be liable for the full amount due even if the company is a corporation or LLC. New Jersey has a similar “responsible persons” framework for trust fund taxes. In short, if your company collected sales tax and didn’t remit it, the state can - and often will - look to you personally.

Sales tax cleanup also matters because some states withhold or slow formal dissolution until tax accounts are settled. New Jersey requires a tax clearance certificate as part of dissolving, and the state notes the process “may take several months.” Pennsylvania likewise requires tax clearance certificates from both the Department of Revenue and the Department of Labor & Industry before filing dissolution documents with the Department of State. If you ignore sales tax, the paperwork that ends your business can stall.

Step 1: Reconcile What You’ve Filed Against What You Actually Collected

Start by pulling your sales, invoices, and bank records for the full period up to your shutdown date. Compare the tax you collected to what you filed in each jurisdiction. Confirm you filed everywhere you had a registration, including local jurisdictions that may require separate filings.

Local filings trip up many teams. In Colorado, for example, more than 70 “home‑rule” cities administer their own sales taxes separate from the state. The Department of Revenue cautions that these self‑collecting jurisdictions often have different rules and require direct contact or separate filings; the state’s DR 1002 publication keeps a current list, and Colorado’s SUTS portal shows which cities accept returns through the unified system. If you sold in home‑rule cities but never filed there, you may have municipal exposure even if your state returns were perfect.

As you reconcile, watch for “zero” periods. Many states require you to file even when you had no taxable sales that month or quarter. Colorado’s guidance is blunt: you must file a return every period - even if no sales were made - otherwise the department may file an estimated return for you. Alabama, Georgia, Missouri, Louisiana, and others have similar rules. If your account sat idle during wind‑down and you didn’t file zeros, expect notices.

Finally, confirm each registration number and the status of every account. If you collected in California, for instance, check CDTFA account status for each location and make sure any use tax obligations on business purchases were reported. If you made tax‑free purchases for use in the business, California expects you to report use tax on your return.

Step 2: File Final Returns and Pay What You Owe - Then Explore Relief Options if Needed

Most states expect a “final return” that runs through the date you stopped making taxable sales. California’s Publication 74 explains how to file a final return and close the account, and it’s crystal clear that closing an account does not wipe away balances - you still must pay any assessed or unreported tax due. Colorado likewise offers online closure for sales tax accounts and a separate form if you prefer paper. Even if your final period is zero, many states still require the final filing to formally close the account.

If you collected tax and never remitted it, pay as part of your final return or contact the agency to arrange payment. Many states offer installment plans. The CDTFA’s payment plan page explains how to set one up and notes special programs (such as interest‑free plans offered during specific periods). New York’s Department of Taxation allows installment payment agreements that you can request online in many cases. Colorado publishes payment plan instructions for taxpayers who cannot pay in full at once. Practical point: interest usually keeps accruing while you’re on a plan, so file and start the process quickly.

If you discover you should have been registered in states where you never filed at all, consider a voluntary disclosure agreement (VDA). States and multistate programs often limit lookback periods and reduce penalties when you come forward before the state contacts you. The AICPA’s Tax Adviser highlights that VDAs are commonly used to close out matters in a sale or dissolution and frequently cap lookback to about three to four years for sales tax. The Multistate Tax Commission’s National Nexus Program coordinates VDAs across participating states, streamlining the process. Washington and other states publish their own VDP details as well. Timing matters: in many programs you must apply before registering or before a state contacts you.

Real‑world Examples Founders Should Know

The risk of personal exposure isn’t theoretical. In State Board of Equalization v. Wirick (California Court of Appeal), the court held that personal liability under Revenue & Taxation Code §6829 arises “upon termination, dissolution, or abandonment” of the business - exactly when many founders are trying to wrap up - underscoring why cleanup must happen before or during dissolution, not after. California’s official annotations and law guide pages echo how §6829 works in practice.

New York’s “responsible person” doctrine is equally active. In a New York Tax Appeals Tribunal case, an officer was found personally liable for sales tax even though she’d been discharged before the due date; the record showed she controlled day‑to‑day finances and handled filings when the tax accrued. New York’s technical guidance reinforces that responsible persons can be liable regardless of whether the business is an LLC or corporation.

On the administrative side, dissolutions can bog down until taxes are cleared. New Jersey’s Division of Revenue states you must request tax clearance, warns it can take months, and provides the forms. Pennsylvania’s instructions say the first step in ceasing business is to obtain tax clearance certificates from Revenue and Labor & Industry; you then file dissolution with the Department of State. If you budget only a few weeks for dissolution paperwork, these clearance steps can easily be your long pole.

Step 3: Cancel or Close Sales Tax Permits - Everywhere You’re Registered

Once final returns are in, close your permits. In California, you close the account or individual locations in your CDTFA online profile; Publication 74 and CDTFA’s online resources outline the process. In Colorado, you can close the sales tax account through Revenue Online or submit the Business Account Closure Form; the site explains that online closures take effect the next business day, while paper takes longer. Alabama’s revenue department explains how to request account closure through its portal (and reminds taxpayers that delinquent returns must be filed). Keep the closure confirmations.

There’s a practical reason to do this promptly: if you don’t close the permit and you don’t file, some states will estimate returns for you and start the collection clock. Colorado says it will file an estimated return on your behalf if you fail to file, and those assessments remain due until you file the real return. That’s how avoidable notices become costly distractions long after operations stopped.

Step 4: Keep Your Records - Audits Do Not End With Dissolution

States can audit sales tax filings for years after you close. Recordkeeping rules vary, but a common pattern is three to four years, longer in certain circumstances. New York requires vendors to keep records for at least three years from the due date or filing date of the return, and the department may require longer if records are part of an audit or case. California tells sellers to keep sales and use tax records for at least four years; its recordkeeping publications and audit guides repeat that standard. Colorado’s “Points of Compliance” brochure instructs retailers to keep resale invoices for three years. Keep sales, exemption certificates, bank statements, and register data aligned with what you reported.

Statutes of limitation often run three or four years from filing, but states can extend or lift those limits in cases like non‑filing or significant underreporting. That’s another reason to file final and zero returns: filing starts the clock.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Closing

One frequent oversight is failing to file zero returns while you wind down. As noted above, many states require a return every period until the account is closed, even with no sales, and will issue estimated assessments if you skip them. Another is assuming your accounting platform or marketplace facilitator remitted everything for you. Marketplaces might remit their own collections, but you may still owe use tax on business purchases or have non‑marketplace sales to report.

Founders also miss local obligations. In home‑rule states like Colorado, a business may need separate municipal filings even if it already filed with the state. If you only filed state returns and ignored municipal licenses, you can expect letters from city treasurers after you close.

The most serious mistake is distributing remaining cash to investors before clearing trust taxes. Because states treat collected sales tax as their money, not yours, they can assess responsible persons - CEOs, CFOs, controllers, and others with control over the funds - if the company can’t pay. Both New York and New Jersey lay out that responsibility explicitly, and New York has enforced it against individuals in contested cases.

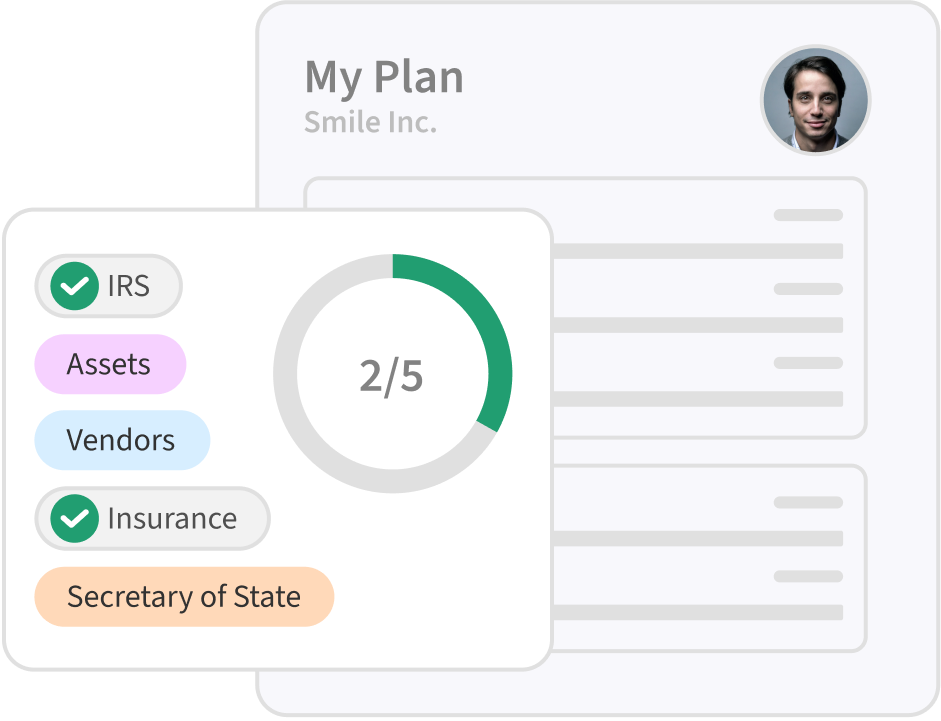

How SimpleClosure Helps Founders Get This Right

For founders in the final stages - often after tough pivots, investor pressure, or a decision to retire - the sales tax piece is easy to delay and surprisingly hard to untangle. We help you centralize sales data, identify every registration, and reconcile filings against what was actually collected, including in tricky local jurisdictions. We then coordinate with your accountant to prepare final returns, close permits, and assemble the proof you’ll want on file for audit windows. When past non‑filing is discovered, we organize the documentation your tax advisor needs to pursue installment plans or voluntary disclosure in the relevant states.

We focus on U.S. SMB tech and software businesses, often venture‑backed, that want a clean, orderly wind‑down. That means we build the sales‑tax work into your broader dissolution plan so tax clearance steps don’t become the pacing item for distributions to investors. We don’t provide legal or tax advice, but we manage the process end‑to‑end so you, your board, and your investors have transparency and a clear path to closure.

Closing Thoughts

Sales tax is one of the most important items to handle before you dissolve a business that ever collected it. It’s a trust tax, so failure to file and remit can follow responsible individuals after the entity disappears. The fix isn’t complicated, but it does require a checklist mindset: reconcile what you collected, file final returns even if they’re zero, close every registration including local ones, and keep good records for the audit window. Where there’s a significant balance or past non‑filing, most states have tools - installment plans, VDAs, coordinated multistate programs - to help you resolve it and move on.

If you’re unsure where to begin, we can help you organize the data, line up the right state‑by‑state actions with your tax professional, and keep your dissolution from stalling for want of a sales tax clearance. Addressing this early will protect you from personal exposure and speed the final steps of your wind‑down.

Note: "This guide is for general information purposes only and should not be taken as legal or tax advice. Regulations vary widely by state and local jurisdictions so be sure to consult with your trusted tax professional on your specific requirements."