Shutting down a company is rarely a decision made overnight. For most founders – especially in tech and software – it follows years of chasing product-market fit, raising capital, building teams, and trying every pivot that made sense. When the final decision to close is made, attention naturally turns to the big, obvious questions: How will we handle employees? What’s left to pay vendors? Have we filed all the right documents?

Then, often toward the end of the process, another question emerges. Sometimes from the board, sometimes from investors, sometimes just from the founder lying awake at night: “Should we make a distribution to our shareholders?”

It sounds straightforward: if there’s cash left over after paying bills, why not return it? But in reality, deciding whether to distribute funds at shutdown is a legal, financial, and strategic decision that depends on much more than what’s in the bank.

Distribution Take-Aways

They can preserve goodwill when they’re transparent and timed while the company is still solvent.

They can create personal risk if any creditor, tax, or wage obligation is left hanging.

They’re easiest to navigate when founders act early, verify who’s actually entitled to proceeds, and close cleanly.

What a Distribution Actually Entails

In startup terms, a distribution is the return of leftover company funds to shareholders once every known liability has been resolved. For venture-backed C-Corporations, this process is often shaped by liquidation preferences set out in investor agreements. Those preferences determine who gets paid first and in what order, sometimes leaving common shareholders with nothing, even when there’s cash on the table.

The order in which distributions happen is often called a “waterfall”, and in many cases, the outcome surprises founders. In this notable case, FanDuel – then a leading daily fantasy sports platform – was subject to liquidation preference dynamics that left founders and common shareholders without upside after what appeared to be a significant sale:

“When the FanDuel founders raised funds, two key investors received liquidation preference that entitled them to the first $559M in an exit…”

While the exact sale price of FanDuel in that context wasn’t publicly confirmed to be exactly $559 million, the implication is clear: investors with liquidation preference walked away fully satisfied before any common shareholders, including founders or employees, received a payout.

This case captures the core risk: liquidation preferences aren't just abstract legal terms. They can – and have – resulted in founders and shareholders walking away with nothing, even in a high-value exit scenario.

When Distributions Make Sense

Distributions typically make sense when the company has no debt, all shutdown expenses are covered, the cap table is accurate and undisputed, and there’s a meaningful amount of cash left to return to shareholders.

While most examples of distributions come from shutdown scenarios, the dynamics of who gets paid – and how much – are also shaped by liquidation preferences in acquisitions. An interesting case is WhatsApp’s acquisition by Facebook in 2014. Though not a closure, it’s a high-profile illustration of how preference structures can dictate payout outcomes. Investors had negotiated 2× participating liquidation preferences, meaning they first received double their investment before participating pro-rata in the remaining proceeds. Even in a $19 billion deal, this significantly favored preferred investors and left common shareholders with far less than they might have expected under different terms.

Pro Tip: Before you even consider a distribution, model your waterfall. Use online tools or spreadsheets to map out exactly how much each class of shareholder would receive. Doing this before announcing any plans can save you from overpromising and underdelivering.

When Distributions Are Risky

Sometimes, making a distribution can open you up to significant problems. If there are unresolved liabilities, such as unpaid taxes, outstanding vendor invoices, or pending litigation, sending money to shareholders can create legal exposure and even personal risk for directors.

A cautionary case involves a Los Angeles hardware startup that returned $100,000 to its investors, only to face an unexpected $80,000 tax bill six months later due to a miscalculation. The IRS came knocking, but the funds were already in investors’ accounts. The founders were left personally liable for the difference, a blow that followed them for years.

Distributions are also risky when equity documentation is unclear. A messy or disputed cap table can spark conflict over who is entitled to what. And if the leftover funds are minimal, the administrative costs of a distribution - legal fees, accounting work, payment processing - can swallow much of it, making the effort pointless.

Pro Tip: If there’s any chance of future claims, consider holding the remaining funds in an escrow account for a set period. This gives you a buffer to handle unforeseen liabilities without trying to claw money back from shareholders later.

The Questions Every Founder Should Ask First

Before deciding to make a distribution, ask yourself:

Have all known debts, taxes, and contractual obligations been paid or accounted for?

Have final state and federal tax returns been filed?

Is your equity documentation clean, complete, and free from dispute?

Is your board fully aligned on making a distribution?

Have legal and financial advisors reviewed the plan for risks you might have missed?

These questions are your guardrails that protect you from making a well-intentioned but damaging move.

Why Process Matters as Much as Outcome

Even if you have the money and the intention, how you handle the process matters just as much as whether you make a distribution. That means maintaining thorough records, communicating early and transparently with investors, and ensuring every step aligns with your legal obligations. In some states, you may be required to notify creditors before making any shareholder payouts. In others, failing to follow formal dissolution protocols can leave your company technically “alive” in the eyes of regulators, leading to ongoing fees and obligations.

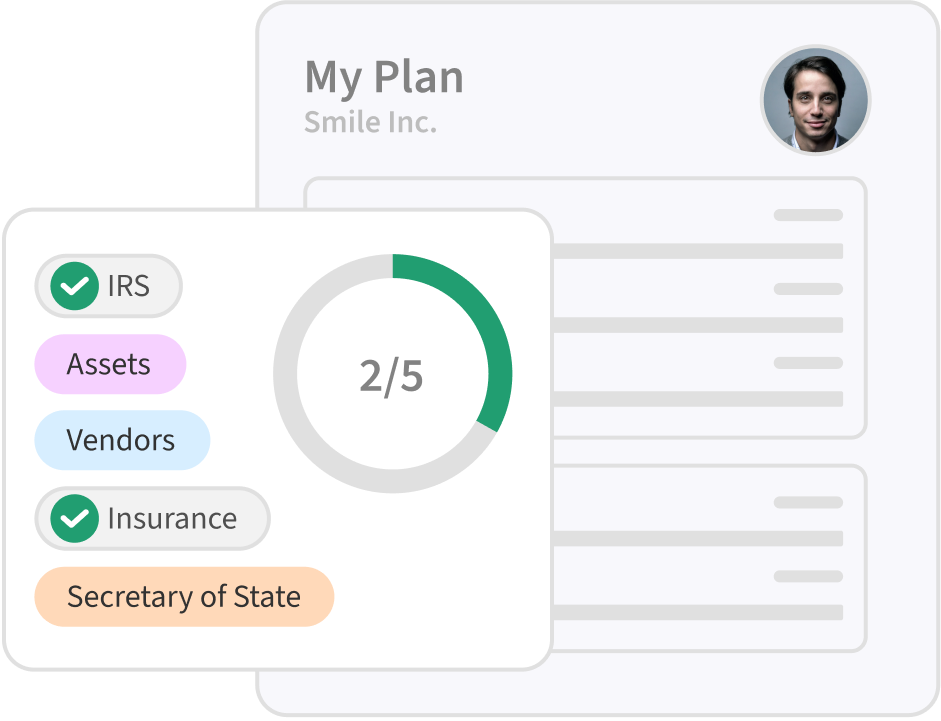

How SimpleClosure Fits Into the Picture

At SimpleClosure, we help founders navigate every stage of winding down, including the tricky question of distributions. Our role is to untangle your finances, ensure your cap table is current, confirm all obligations are met, and then determine whether a distribution is both possible and advisable. When it is, we help coordinate with your board, investors, and legal advisors to ensure everything is documented and compliant. While we’re not a law firm, our in-house dissolution experts bring years of experience guiding founders through shutdowns, helping them return funds 5x more quickly and cleanly than they expected.

Closing with Integrity

Distributions aren’t just about money – they’re about closing a chapter with clarity and integrity. When done right, they can reinforce trust with investors and pave the way for future opportunities. Done wrong, they can leave a trail of liabilities, strained relationships, and reputational damage that lingers long after the company is gone.

If you’re considering a distribution during your shutdown, don’t treat it as a last-minute decision. Approach it with the same diligence and transparency you brought to raising capital in the first place. And if you’re unsure whether it’s the right move, get expert advice before you commit. The way you close your company can speak volumes about the way you ran it, and that legacy will follow you into your next venture.

Get your free founder's guide to shutting down

A comprehensive breakdown of how founders can quickly and easily execute a fully compliant shutdown