When a company shuts down, the to‑do list can feel endless: board consents, final payroll, tax filings, and more. What rarely gets equal attention is the decision to keep, cancel, or extend insurance. Yet the legal and financial residue of a startup’s life doesn’t respect a shutdown date.

Consider Katerra, the SoftBank‑backed construction startup that filed Chapter 11 on June 6, 2021. Within days, former employees filed a WARN Act class action over the abrupt layoffs, keeping the company in court despite the lights being off and the doors shut. This is the terrain where “tail” insurance matters. It’s not glamorous, but for many founders it is the cleanest way to avoid paying for yesterday’s problems with tomorrow’s savings.

Two Clocks: Occurrence vs. Claims‑Made

Most founders buy insurance without thinking about triggers, but the trigger is everything.

Occurrence‑based coverage (like a typical general liability policy) is tied to when the injury or damage happened. If a customer is injured while your policy is active, the policy that was in force at the time of injury responds.

Claims‑made coverage (which includes D&O, E&O/professional liability, EPLI and much of cyber) works the other way: the policy only responds if the claim is made while the policy is alive, and many forms also require that you report it within a short, specified window. Miss the window, and you can forfeit coverage entirely. This IRMI primer captures this timing difference crisply and even cites the Harvard v. Zurich case, where a university lost excess coverage for reporting to an insurer after the claims‑made reporting deadline.

Because so many startup‑critical policies are claims‑made, a simple cancellation at shutdown can be risky. You stop paying premium, but you also stop having coverage for claims that arrive the day after your last policy expires.

What a “Tail” Really Is (And Isn’t)

Tail insurance is industry shorthand for an extended reporting period, or ERP. In other words, tail coverage lets you report post‑expiration claims arising from pre‑expiration acts; it does not reinstate the aggregate limits and it does not cover acts committed during the tail.

Duration can be negotiable. For directors’ and officers’ liability (D&O), a six‑year tail is widely treated as the U.S. standard, particularly around M&A or a formal wind‑down. The reason is practical: it spans common statutes of limitation for fiduciary duty and contract claims, and it tracks what acquirers, lenders, and indemnification agreements typically expect.

Price is also predictable enough to budget. Brokers often quote tails as a one‑time multiple of the last annual premium paid up front, and most crucially, non‑cancellable. In ordinary private‑company deals, six‑year D&O runoff has historically run around 175%–225% of the expiring annual premium, and hard markets can push options toward or past 300%.

When a Tail Earns Its Keep

If your board, officers, or investors could still be sued over past decisions, a tail is worth consideration. Delaware’s statute gives corporations broad power to indemnify directors and officers, but that promise is only as good as the balance sheet. If the entity is dissolved or insolvent, indemnification may be unavailable, and Side A of a D&O program – kept alive via a tail – is often the only practical funding source for defense and settlement.

Timing realities also favor tails in data‑heavy businesses. Claims don’t arrive the day bad things happen. IBM’s 2024 breach study found a global mean of 258 days to identify and contain a breach, with incidents involving stolen credentials taking roughly 292 days. That lag dwarfs the short, automatic 30–90‑day “basic ERP” many policies provide for free.

Finally, some exposures simply don’t respect a closing date. Employment claims, privacy claims, and investor disputes can be filed after the last day of operations. The Katerra WARN class action, mentioned earlier, illustrates the point: the suit landed in mid‑June 2021 within days of the bankruptcy filing, not months into an ongoing renewal cycle. A tail is designed for exactly that kind of after‑the‑fact filing.

Line‑By‑Line: What to Keep, Cancel, or Extend After Closing

Start with D&O. It is almost always written on a claims‑made form. Change‑in‑control provisions typically flip the policy into “run‑off” for pre‑close acts and shut off coverage for anything that happens after the effective date; buying the tail then extends the time to report pre‑close claims for years. In negotiated exits, merger agreements often require a six‑year tail and sometimes cap the premium. If your company is dissolving rather than selling, you won’t have a counterparty setting terms, but the risks are the same: directors and officers can still be named long after dissolution, and the tail is the only way to preserve the defense wallet.

Professional liability – tech E&O, management consultants’ E&O, and similar forms – shares the same claims‑made DNA. If your software, design, or advice could later be blamed for a customer’s loss, tailing the policy is worth pricing. Law‑firm and broker guidance on ERPs is consistent: an ERP lets you report new claims about past “wrongful acts,” it usually must be elected promptly after the policy ends, and it does not add fresh limits.

Cyber is also commonly claims‑made. Policies sometimes call the tail a “discovery period,” but the mechanics are the same: without an ERP, a post‑shutdown claim about a pre‑shutdown incident can fall into a gap. Counsel and insurers have been urging companies to line up discovery periods when swapping cyber carriers for years; the logic is even stronger when you’re shutting down. Pair that with the breach‑detection lag data above, and it’s clear why founders in data‑heavy verticals should at least request quotes.

Employment practices liability (EPLI) is typically claims‑made as well. If layoffs were part of your winding‑down plan, you are still in the look‑back period for wrongful termination, discrimination, retaliation, or wage‑and‑hour claims. Many policies give you only a short window to elect an ERP after expiration; brokers frequently express ERP pricing as a percentage of the last annual premium. That window closes fast when a company is dissolving and the finance team is scattering.

General liability deserves a more nuanced conversation. It is often occurrence‑based, which tempts people to cancel it immediately. But, occurrence coverage only responds if the injury or damage occurs while the policy is in force. If someone is hurt by a product six months after you cancel your CGL, the old policy won’t respond merely because you manufactured the item last year. Risk texts are blunt on this point: products‑completed operations coverage does not extend the policy period; it must be in force when the bodily injury or property damage occurs. That’s why some companies consider “discontinued products and operations” coverage after they stop selling or building.

How to Make the Decision Without Turning It Into a Second Job

The disciplined way to approach this is to treat wind‑down like a miniature diligence process.

Start by inventorying every policy, flagging which ones are claims‑made and which have change‑in‑control triggers. Read the declarations page for the ERP election window and any pre‑negotiated ERP pricing. Ask your broker for tail quotes early, because carriers won’t be moved by your operating calendar or dissolution date.

Then put the options in front of your board with a recommendation and a clean record of the vote. The reason for a record is simple: if someone challenges the adequacy of protection later, you want to show a thoughtful, documented process.

Where SimpleClosure fits

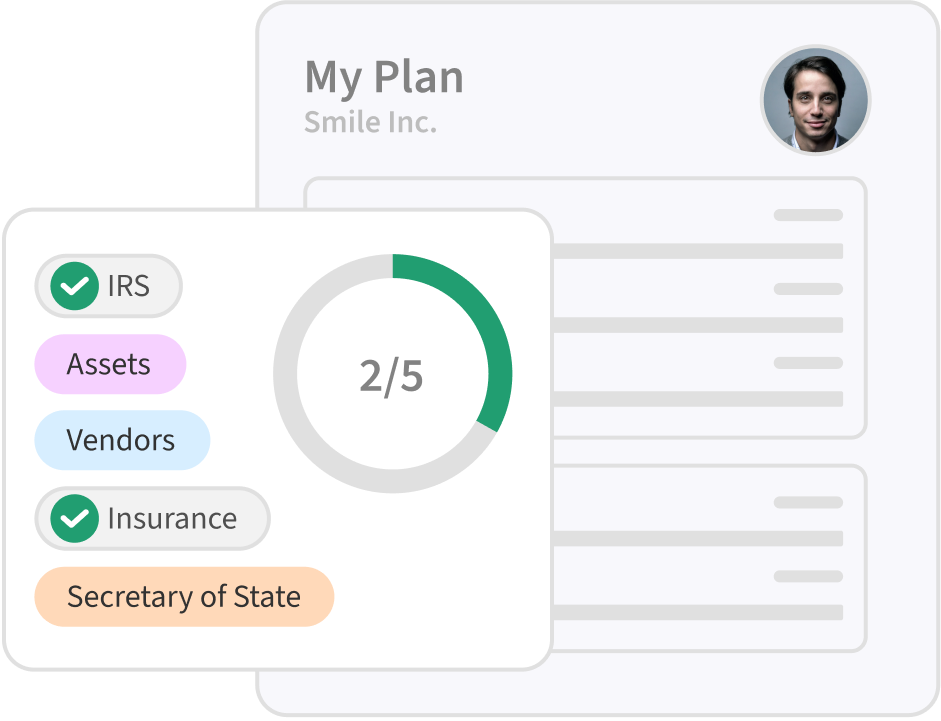

Founders shouldn’t have to memorize insurance jargon on the way out. In our close‑down workflows, we help catalog active policies, label the claims‑made forms, and surface contracts that might obligate you to keep coverage in place.

We also calendar the decision windows that matter. 30–90‑day ERP election periods are easy to miss once finance, HR, and leadership are moving on. We store the binders, endorsements, and board consents alongside your tax and dissolution files so you can prove months later, what you bought and why. The goal is to make sure nothing slips through a procedural crack at the last minute.

If you’re approaching a wind-down and need help securing tail coverage, SimpleClosure has partnered with Vouch to make the process easier. Vouch specializes in D&O and wind-down insurance and can often provide coverage even if your original policy came through another broker. Their tail policies can protect directors and officers from investor lawsuits, creditor claims, or regulatory investigations that may surface months or years after your company shuts down.

And if you don’t currently carry D&O insurance, you may still qualify for what’s known as standalone or “naked” tail coverage. Vouch provides guidance on this option and can generate quotes even if you never had an active policy in place. Don’t have existing D&O coverage or want to explore a quote from our partners at Vouch? Click here to learn more.

Closing Thoughts

Shutting down a business is about finishing things, but insurance is about what remains unfinished: uncertainty. A well‑chosen tail turns those lingering risks into a prepaid commitment that protects your board and officers into their next chapters. For most venture‑backed tech companies, that means a serious look at a six‑year D&O tail, a practical review of E&O and cyber if you handled customer data or code, and in some cases, discontinued-products coverage if what you built could cause harm after closing. The right answer is specific to your facts and contracts – but the wrong answer is to let coverage lapse and hope that yesterday’s decisions stay buried.

This article is for general information, not legal or insurance advice. We recommend working with qualified counsel and a licensed broker for decisions on your specific situation.